TRAAP2

TRAAP2: Tranexamic Acid for the Prevention of Blood Loss after Cesarean Delivery

Sentilhes L. New Eng J Med 2021; 384:1623-1634. doi:0.1056/NEJMoa2028788

Clinical Question

- In patients undergoing cesarean section (CS) does the administration of tranexamic acid (TXA) when compared to a placebo result in a lower incidence of calculated estimated blood loss or red blood cell transfusion by day 2?

Background

- The use of TXA has been widely studied in post partum haemorrhage (PPH)

- The WOMAN trial showed that TXA may be beneficial in reducing the risk of death due to PPH

- This has been lauded as a landmark trial but there are some controversies that are excellently summarised here

- The evidence surrounding the use of TXA post CS is limited and consists mainly low quality evidence and there is no strong evidence to support its use in a prophylactic manner

Design

- Multi-centre, randomised, placebo controlled, double blind trial

- Randomised to receive uterotonic agent plus either TXA or placebo

- Randomised in 1:1 ratio

- Computer based, in blocks of 4

- Stratified by site and whether CS done pre or during labour

- TXA and placebo in identically labelled packaging and vials

- Appropriate consent process – written informed consent obtained by treating teams if CS considered likely

- Blood loss estimated using following equation:

- Estimated blood volume x [(pre-op haematocrit-post-op haematocrit) / post-op haematocrit]

- Pre-op haematocrit was most recent in 8 days prior to caesarean

- Post-op was closest to day 2 post delivery

- Physician responsible for the delivery prospectively recorded the procedures used during the third stage of labor and clinical outcomes identified in the immediate postpartum period

- Adverse events were assessed until hospital discharge and a telephone interview was conducted at 3 months post delivery

- 4525 patients required

- 4072 patients estimated (80% power to detect a 20% relative difference in incidence of primary outcome, with 5% type 1 error rate)

- Allowed for up to 10% to be lost to follow, deliver vaginally or not have blood tests taken on day 2

- Predominantly based on data from ECSSIT trial

- Performed with modified intention to treat population

- Those who withdrew consent, delivered vaginally, or deemed ineligible after randomisation were excluded

- There were two pre-specified pre-protocol populations: those who received TXA within 3 minutes and those who received TXA within 10 minutes

- Registered with clinicaltrials.gov NCT3431805

Setting

- 27 centres in France

- March 2018 – January 2020

Population

- Inclusion:

- > 18 yo

- >/= 34 weeks gestation

- expected to undergo Caesarean before or during labour

- Exclusion:

- Known or suspected increased risk of VTE / arterial embolism

- Increased risk of bleeding (including administration of LMWH or anti-platelet in week prior)

- History of seizures or epilepsy

- Eclampsia

- Autoimmune disease

- Failed operative vaginal delivery

- Sensitivity to trial drugs

- Hb < 9g/dL in the week prior

- Poor comprehension of spoken French

- 4551 randomised

- 2276 – TXA

- 2275 – placebo

- Baseline demographics similar

- Age: 33.3 (TXA) vs 33.5 (Placebo)

- BMI: 26.3 vs. 26.1

- Primip: 37.2% vs. 36.6%

- Prior CS: 51.8% vs. 52.4%

- History of PPH: 5.1% vs. 4.5%

- Multiple pregnancies: 7.2% vs. 7.2%

- Timing of CS – during labour: 28.9% vs. 29.2%

- GA: 3.0% vs. 3.8%

- Prophylactic uterotonic: 98.9% vs. 99.0%

- Anticoagulant prophylaxis post delivery: 58.8% vs. 59.1%

- Median duration of interval from birth to TXA: 2 mins vs. 2 mins

Intervention

- 1g TXA

- 10ml vial

Control

- Normal saline

- Identically labeled vial

Management common to both groups

- Either TXA or placebo given over 30-60 seconds in the first three minutes after birth

- This was given after bolus prophylactic uterotonics given (5-10u oxytocin or or 100 μg of carbetocin)

- Subsequent oxytocin infusion at discretion of treating unit

- All spent at least 2 hours in PACU / Recovery until bleeding diminished to expected amount

Outcome

- Primary outcome:

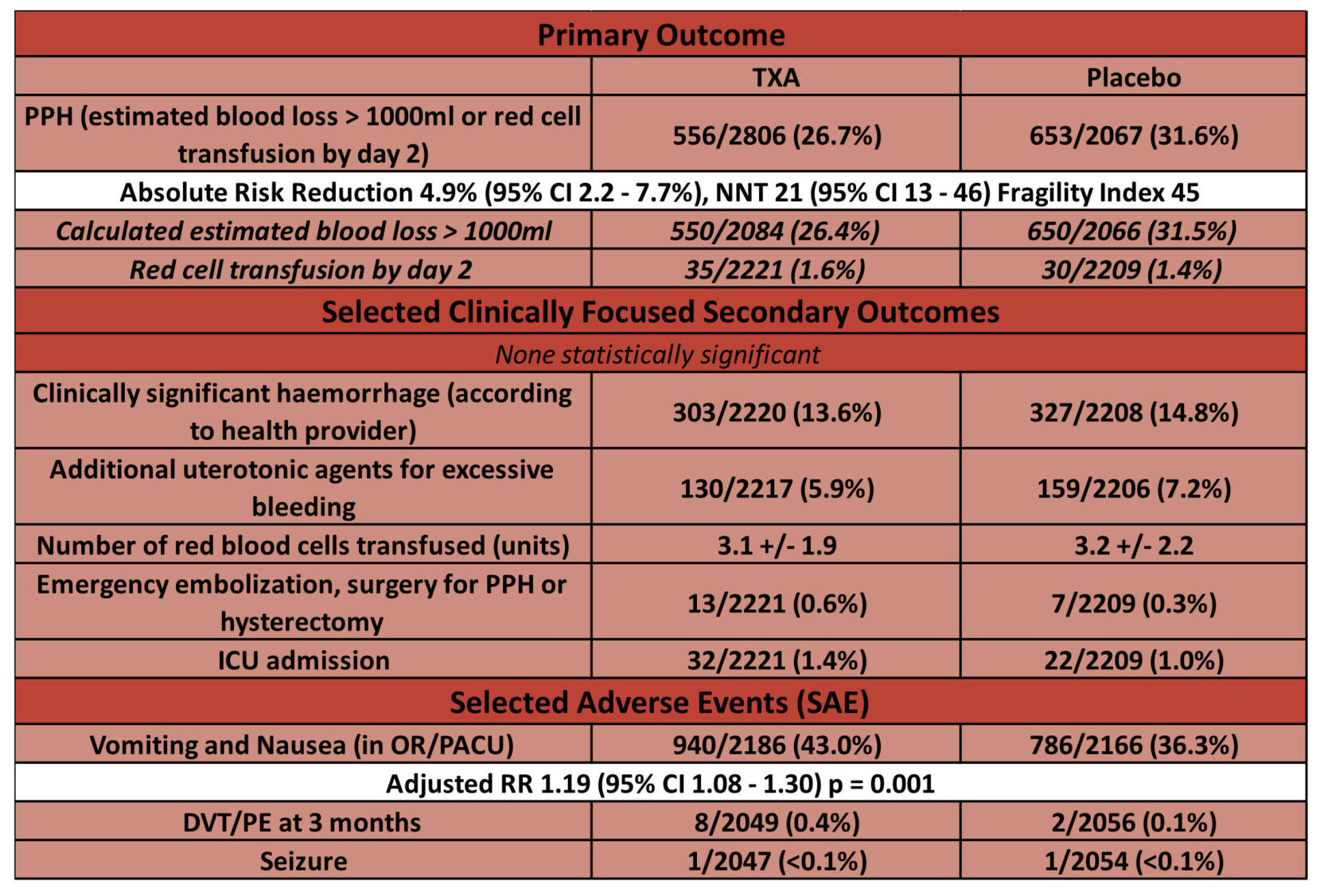

- Postpartum hemorrhage (defined as a calculated estimated blood loss greater than 1000 ml or red-cell transfusion by day 2): – significantly reduced in tranexamic acid group

- 556/2086 (26.7%) TXA vs. 653/2067 (31.6%) Placebo

- Adjusted RR 0.84 (95% CI – 0.75 – 0.93, p = 0.003)

- No difference between pre-specified subgroups (PPH risk and timing of CS)

- Secondary outcomes:

- No significant differences in:

- Gravimetrically estimated blood loss: 689ml vs. 719ml

- Estimated by suction volume and swab weight

- Clinically significant blood loss: 13.6% (TXA) vs. 14.8% (Placebo)

- Additional uterotonic agents for excessive bleeding: 5.9% vs. 7.2%

- Blood transfusion: 1.9% vs. 1.8%

- Number of units transfused: 3.1 vs. 3.2

- Gravimetrically estimated blood loss: 689ml vs. 719ml

- Significant difference in pre and post-operative Hb:

- Peripartum change -1.2 g/L vs. -1.4g/L (p < 0.001)

- No significant differences in:

- Adverse Events:

- In PACU or OR:

- Higher rates of nausea and vomiting

- 43.0% vs. 36.3% (p < 0.001)

- Higher rates of nausea and vomiting

- D2 after delivery:

- No significant differences between groups for urea, creatinine, AST, ALT

- Up to 3 months after delivery:

- No significant difference for:

- Seizure: <0.1% vs. <0.1% (1 in each arm)

- DVT/PE: 0.4% vs. 0.1% (8 cases in TXA arm, 2 in placebo)

- No significant difference for:

- In PACU or OR:

Authors’ Conclusions

- The use of TXA in this setting reduced the incidence of PPH (as defined by calculated estimated blood loss > 1000ml or red cell transfusion by day 2).

- However there was no reduction in clinical secondary outcomes

Strengths

- Large, multi-centre trial

- Well balanced balanced baseline characteristics

- High proportions of risk factors for PPH (previous caesarean, prior PPH, obesity, multiple pregnancy, emergency caesarean) present in baseline characteristics

- This is important to ensure that two low risk cohorts not being analysed

- Sensible pre-specified subgroup looking at the use of TXA in those at high risk of PPH vs. low risk

- Defined as presence of a one or more risk factor with an OR > 3

- Good randomisation and blinding strategy results in strong internal validity

- Pragmatic statistical analysis plan

- Although large numbers of women were randomized but not assessed for the primary outcome in the modified intention to treat analysis, the statistical analysis plan allowed for up to 10% drop out following randomisation

- Sensible use of a standardised method of estimating blood loss given clinicians’ estimations are often incorrect

- The values of estimated blood loss obtained by the gravimetrical method (suction volume, and weighing swabs) and the standardised equation similar

- Minimal cross-over / protocol violations

- Only 1.4% in each group received no treatment

- Only 0.1% in each group received the opposite treatment

- Good follow up at three months – important for reporting adverse events

- 93.5% (TXA) vs. 94.4% (Placebo) completed follow up interviews at three months

Weaknesses

- The primary outcome is not patient orientated

- Although the trial is not adequately powered for clinically relevant secondary outcomes there is no suggestion that TXA reduces the rate of these

- The authors rightly acknowledge this in the conclusion

- Although the trial is not adequately powered for clinically relevant secondary outcomes there is no suggestion that TXA reduces the rate of these

- As discussed, the statistical plan allowed for up to 10% drop out from those who are randomised to receive a treatment, however:

- The rates were slightly higher than 10% in each arm:

- TXA – 10.5%

- Placebo – 11.8%

- This may introduce an attrition bias

- 210 (4.6%) patients excluded for unknown reasons or meeting exclusion criteria following randomisation

- This may introduce a selection bias

- 278 (6.1%) had missing data for the primary outcome

- The appendix has a comparison of where only complete cases are analysed (the data presented above) against the imputation of missing values as failures (i.e. they were assumed to have PPH)

- If the missing values are treated as failures then the p value > 0.005

- TXA 31.1% vs Placebo 36.0% p = 0.006

- If the missing values are treated as failures then the p value > 0.005

- The appendix has a comparison of where only complete cases are analysed (the data presented above) against the imputation of missing values as failures (i.e. they were assumed to have PPH)

- The rates were slightly higher than 10% in each arm:

- PPH is a heterogenous process

- The 4Ts is a common acronym for PPH reasons: uterine tone, retained tissue, trauma, thrombin

- TXA does not have a plausible biological mechanism of action in the treatment of PPH for anything other than trauma

- No documentation of suspected reasons for PPH is recorded

- The protocol allowed for the use of a oxytocin infusion as per local hospital policy following the uterotonic bolus

- No mention is made of how many had an oxytocin infusion after

- This could be an important confounder

- No mention is made of how many had an oxytocin infusion after

- The 4Ts is a common acronym for PPH reasons: uterine tone, retained tissue, trauma, thrombin

- The study excluded those who are increased risk of bleeding – would these patients potentially benefit more?

- The BNF suggests that TXA should be given as a slow IV injection (at a rate not exceeding 100mg/minute)

- The protocol states it should be given over 30 to 60 seconds (20x as fast)

- This may be a reason for the increased rate of vomiting and nausea

- The protocol states it should be given over 30 to 60 seconds (20x as fast)

- Approximately 25% did not receive TXA within three minutes in each arm

- This is understandable as it is an already frenetic time ensuring that uterotonics are given, and that the baby and parents are well!

- This delay did not seem to have an effect though as in the protocol analysis which included those who received TXA/placebo within 10 minutes still showed a significant reduction in the primary outcome

The Bottom Line

- The use of prophylactic TXA for caesarean delivery reduces the rates of PPH as defined by an estimated blood loss of > 1000ml or red cell transfusion by day 2

- I will not use TXA in a routine prophylactic manner given this did not seem to show any trend to a reduction in meaningful clinical outcomes, and an increased risk of nausea and vomiting

External Links

Metadata

Summary author: George Walker

Summary date: 9th May 2021

Peer-review editor: David Slessor

Image by: iStock