DEVICE

Video versus Direct Laryngoscopy for Tracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults

Prekker. NEJM 2023 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2301601

Clinical Question

- In critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, does the use of a videolaryngoscope (VL) compared to a direct laryngoscope (DL) improve the first-pass success rate?

Background

- 5 million critically ill adults undergo tracheal intubation outside of the operating theatre in the US annually

- Failure to intubate the trachea on the first attempt is associated with worse outcomes for this patient cohort, and occurs in as many as 20 to 30% of patients

- Numerous previous studies and systematic reviews have demonstrated that VL is associated with improved overall success rates and lower complication rates in theatre and non-theatre settings

- However, routine adoption of videolaryngoscopy in the critically ill still varies globally, and opinions on whether effectiveness thresholds have been reached remain divided

Design

- Pragmatic, multicentre, unblinded, randomized, parallel-group trial

- Randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to undergo intubation with VL or DL

- Permuted blocks of variable size and stratified by trial site

- Sequentially numbered opaque envelopes, with allocation remaining concealed until after enrolment

- Blinding of intubators and outcome assessors not possible

- Data collected by trained observer, except operator reported anticipated difficulty, Cormack-Lehane grade, reasons for failure, procedural complications and number of previous intubations previously performed

- Sample size calculation:

- 80% successful first attempt at intubation in DL group and 4% loss to follow up would require 2000 patients to be enrolled to detect an absolute difference of 5% in the primary outcome

- This is based on prior trials, alongside expert opinion as to what a clinically meaningful difference in first pass success is

- A single interim analysis was planned to be performed after 1000 patients had been enrolled with prespecified stopping rule (p value ≤0.001 for the difference between the groups in the primary outcome)

- Registered with ClinicalTrials.gov and requirement for written consent waived

Setting

- 17 sites (10 ICUs and 7 EDs) in the USA

- March – November 2022

Population

- Inclusion:

- Patient located in a participating unit

- Planned procedure is orotracheal intubation using a laryngoscope

- Planned operator is a clinician expected to routinely perform tracheal intubation in the participating unit

- Exclusion:

- < 18 yo

- Pregnancy

- Prisoner

- Immediate need for tracheal intubation precludes safe performance of study procedures

- Use of either VL or DL is required, or contraindicated for the optimal care of the patient

- 1947 patients assessed for eligibility, 1908 patients met inclusion criteria, 1420 patients randomised

- 707 randomised to VL, 713 randomised to DL

- 3 patients discovered to be prisoners after randomisation therefore excluded

- 707 randomised to VL, 713 randomised to DL

- Well balanced baseline characteristics (comparing VL vs DL groups):

- Median age: 54 vs 55

- Intubation Location:

- ED: 70 vs 69%

- ICU: 30 vs 31%

- Indications for intubation:

- Altered mental status (45% vs 46%), acute respiratory failure (31% vs 30%), emergency procedure (6 vs 7%), cardiac arrest (5 vs 7%).

- Median APACHE II score: 16 vs 16

- Anticipated difficulty of intubation:

- Easy (33 vs 31 %), Moderate (45 vs 47%), Difficult (10 vs 9%)

- Subjective, global clinical assessment made by the intubator before randomization

- Intubation characteristics:

- Relatively inexperienced intubators

- Median number of previous intubations performed: 50 vs 50

- Resident physician intubator, number: 73% vs 71%

- Proportion of prior intubations with VL:

- < 0.25: 6 vs 5%

- 0.25 – 0.75: 57 vs 60%

- 14% of VL group used hyperangulated blade

- 96% received neuromuscular blockade in both groups

- Adjuncts:

- Stylet: 55 vs 48%

- Bougie: 42 vs 47%

- Relatively inexperienced intubators

Intervention

- Videolaryngoscope at first attempt

- VL defined as a laryngoscope with a camera and a video screen

- Protocol did not specify the brand of VL or the shape of the blade

- Operators instructed to view the video screen during procedure

Control

- Direct laryngoscope at first attempt

- DL defined as a laryngoscope without a camera or a video screen

- Protocol did not specify the brand of DL or the shape of the blade

Management common to both groups

- A stylet or bougie was routinely used during the first tracheal intubation attempt

- Waveform capnography or colorimetric end-tidal carbon dioxide detection was used for confirmation

- All other aspects at the discretion of the treating clinicians, including type of laryngoscope used on subsequent attempts

Outcome

- Stopped enrolment at first interim analysis (1000 patients) because the prespecified stopping criterion for efficacy was met

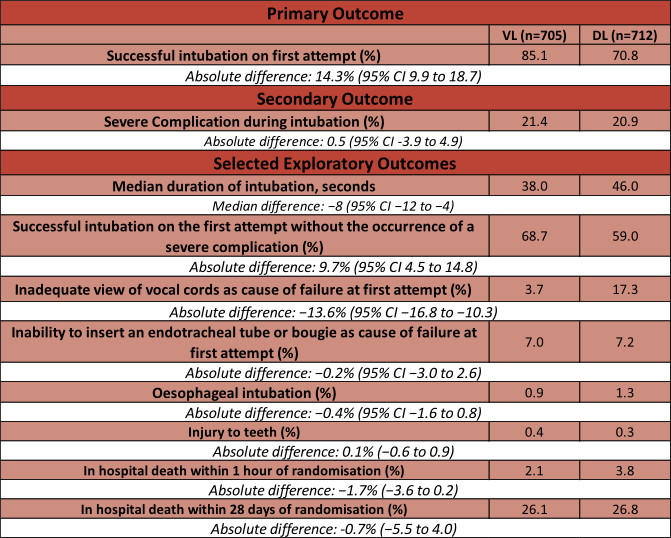

- Primary outcome – Successful intubation on the first attempt

- Defined as the placement of an endotracheal tube in the trachea with a single insertion of a laryngoscope blade into the mouth followed by single insertion of an endotracheal tube into the mouth with or without the use of a bougie prior

- Significantly greater in VL arm

- 85.1% (VL) vs 70.8 % (DL)

- Absolute risk difference: 14.3% (95% CI 9.9 to 18.7; P <0.001)

- Secondary outcome: Occurrence of severe complications between induction and 2 minutes after intubation

- Severe complications defined as:

- peripheral oxygen saturation <80%

- systolic blood pressure <65 mm Hg

- new or increased use of vasopressors

- cardiac arrest or

- death

- No significant difference:

- 21.4% (VL) vs 20.9 % (DL)

- Absolute risk difference 0.5 (95% CI -3.9 to 4.9)

- Severe complications defined as:

- Subgroups :

- All favoured the use of VL except if < 0.25 of all intubations performed prior with a VL and for those with > 100 previous intubations

- Other subgroups included patient location (ED vs ICU), BMI (< 30 or >30), Traumatic Injury, and anticipated difficulty

Authors’ Conclusions

- In this trial, among critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation in an emergency department or ICU, the use of a video laryngoscope resulted in a higher incidence of successful intubation on the first attempt than the use of a direct laryngoscope

Strengths

- Robust design and execution

- Large sample size with minimal loss to follow up

- Minimal protocol deviations and cross-over

- only 8 patients crossed from DL to VL

- Intention-to-treat primary analysis

- Pragmatic design

- Decision as to what type of VL/DL to use left to intubating clinician

- This is both a strength as it improves generalisability and a limitation (see below).

Weaknesses

- Choice of blade left to intubating clinician:

- This introduces a degree of heterogeneity, although the authors explored this heterogeneity with a subgroup analysis

- Unclear what factors drove the choice of blade as most sites had both a Macintosh-style and hyperangulated VL available; only one ICU site had no hyperangulated VL availability (see Supplementary appendix)

- Open-label design:

- Understandably not possible to blind intubators to the device, however some efforts could have been made in attempting to blind outcome assessors for certain outcomes

- Choice of primary outcome

- First-pass success is a commonly used outcome in airway management trials however strictly not a patient orientated outcome

- There is potential for this outcome to be gamed (such as giving up easily on the first attempt with one device or persisting for a prolonged period of time with another to achieve success on the first attempt). This is especially important for non-blinded studies

- A more robust primary outcome may have been first pass success without complications; notably, DEVICE did assess this as an exploratory outcome and the 95% CI was in favour of VL

- Lack of generalisability due to the skill mix and prior experience of intubators

- An imbalance of experience in favour of videolaryngoscopy is likely due to the relative inexperience of intubators and an overall shift towards more liberal VL use in 2022, when the study recruited all its participants

- This is evidenced by the reported proportions of previous intubations done with VL

- Only 6.3% and 4.8% of intubations with VL and DL, respectively, were done by a clinician with previous proportion of DL intubations of more than 25% (see Table 2)

- Interestingly, this is in contrast to a number of the studies included in the Cochrane review, where the imbalance in experience was mostly in favour of DL

- Furthermore, subgroup analyses demonstrated a trend towards the line of null effect for more experienced intubators who have completed more than 100 intubations previously (see Figure 2 and S4)

- If this minority cohort (15% for both VL and DL) were better represented in the study, it is possible that the effect estimated would have shifted closer to the null

- Overall low first-pass success:

- Likely a reflection of relative intubator inexperience (with both devices)

- Unclear whether these findings would directly translate to systems with higher first-pass success rates with any device, or to systems where anaesthetists are primarily performing tracheal intubations outside of theatre

The Bottom Line

- Videolaryngoscopy improves first pass success in critically ill patients undergoing tracheal intubation by relatively inexperienced intubators

- It strengthens much of what is already known on the topic of VL and some of the exploratory subgroup analyses may help dispel certain myths (e.g. good view but cannot intubate)

- It will not considerably affect my practice as I already use a VL (Macintosh-style or hyperangulated VL, depending on patient characteristics) when intubating patients in the ED or ICU

External Links

- article Video versus Direct Laryngoscopy for Tracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults

- further reading The Importance of First Pass Success When Performing Orotracheal Intubation in the Emergency Department

- further reading Intubation Practices and Adverse Peri-intubation Events in Critically Ill Patients From 29 Countries

- further reading Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for adults undergoing tracheal intubation

- further readng Efficacy and adverse events profile of videolaryngoscopy in critically ill patients: subanalysis of the INTUBE study

Metadata

Summary author: Jan Hansel @VirtueOfNothing

Summary date: 21st June 2023

Peer-review editor: George Walker

Picture by: iStock