ARREST

Advanced reperfusion strategies for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and refractory ventricular fibrillation (ARREST): a phase 2, single centre, open-label, randomised controlled trial

D Yannopoulos et al. The Lancet 2020; https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32338-2

Clinical Question

- In adults suffering out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) presenting with an initial rhythm of VF or pulseless VT, does the implementation of early ECMO facilitated resuscitation compared to standard ACLS resuscitation improve survival to hospital discharge?

Background

- OHCA has a well documented poor survival rate

- The PARAMEDIC 2 trial showed a 30day survival rate of 2.8% for all cause OHCA

- Half of all patients with VF and OHCA have refractory VF which has a much worse prognosis

- The evidence for the use of ECMO in OHCA is from observational cohort studies with no randomised trials to date

- ELSO survival to hospital discharge in 2016 registry database for OHCA refractory was 29% for 2885 cases

- Other studies looking at ECMO and PCI in OHCA show survival rates to hospital discharge from 5.5% to 45% for all cause OHCA

- In those that reported VF/VT this ranged 29% to 55.6%

- These are small studies ranging from 7 – 234 patients

- The 2CHEER trial published this year (both OHCA and IHCA with presumed cardio-respiratory origin), showed 44% of patients had survival to hospital discharge with a favourable neurological outcome

Design

- Phase 2, single centre, open-label RCT

- On hospital arrival, member of study team would verify eligibility and randomisation would occur

- Computer generated randomisation schedule

- Random permutations in blocks of 2,4,6

- Functional assessment at 3 and 6 months done by qualified assessors blinded to group allocation

- Pre-specified secondary outcomes included:

- Survival and favourable neurological outcome (mRS 3 or under) at 3 and 6 months post discharge

- Favorable defined as Modified Rankin Score (mRS) 3 or under and Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) Scale 2 or under

- Survival and favourable neurological outcome (mRS 3 or under) at 3 and 6 months post discharge

- All major adverse events recorded

- Registered with ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03880565

- Emergency consent process – had to provide written informed consent within 24 hours of waking

- Mixed Bayesian and Frequentist statistical analysis

- Primary outcome analysed every 30 participants using Bayesian statistics

- Initial 30 patients will be approximately randomised in 1:1 ratio to ensure balance

- Subsequent Bayesian analysis (conducted every 30 patients) will determine ratios moving forward based on posterior probabilities generated (for both outcomes, namely ECMO is better than ACLS and vice versa)

- i.e. if posterior probability that ECMO better is 0.58, and the posterior probability that ACLS better is 0.42, the next 30 randomisation will be weighted 58:42 towards ECMO

- This prevents too many patients being randomised to an inferior treatment

- i.e. if posterior probability that ECMO better is 0.58, and the posterior probability that ACLS better is 0.42, the next 30 randomisation will be weighted 58:42 towards ECMO

- Data safety and monitoring board alerted if at any of these reviews the posterior probability is > 0.986 (i.e. 98.6% probability that either ECMO better than standard ACLS or vice versa)

- Sample size calculated at 174 patients

- This is based on ECMO survival being 37% and ACLS 12%, with 90% power and type 1 error rate of 0.05 and allowing 15% withdrawal and false positive activation rate

- Secondary outcomes analysed using frequentists statistics

- Primary outcome analysed every 30 participants using Bayesian statistics

Setting

- University of Minnesota Medical Center, USA

- August 2019 – June 2020

Population

- Inclusion:

- Adult patients (known or presumed) 18 – 75 years old

- Initial rhythm of VF or pulseless VT

- No ROSC after 3 shocks

- ROSC after >4 shocks did not result in exclusion

- Body habitus able to support mechanical CPR

- Estimated transport time < 30 minutes

- Exclusion:

- Valid DNACPR

- Mechanisms: Drowning, blunt or penetrating trauma, burns, overdose

- Pregnancy

- Terminal Cancer

- Active GI or internal bleeding

- Prisoner or nursing home resident

- Cath Lab unavailable, absolute contraindications to emergent angiography or contrast allergy

- 36 patients assessed > 30 patients enrolled and randomly assigned (15 in each arm)

- 6 excluded: 2 patients had PEA, 1 had transport time of 48 minutes, 3 ROSC after second shock

- One patient withdrew consent prior to discharge in ECMO group

- Baseline Demographics similar (ECMO v ACLS)

- Mean age: 59 v 58

- Male: 93% v 73%

- Coronary Artery Disease: 13% v 27%

- CABG: 13% v 7%

- PCI: 7% v 7%

- Hypertension: 13% v 33%

- Renal Disease: 0% v 13%

- Unknown history: 53% v 33%

- Smoking: 7% v 27%

- Alcoholism: 20% v 0%

- Rates of diabetes, respiratory disease, known medication use similar

- Cardiac arrest (pre-hospital characteristics)

- Public location: 53% v 53%

- Bystander witnessed: 73.3% v 86.7%

- Bystander CPR: 86.7% v 80.0%

- Pre-hospital endotracheal intubation: 33.3% v 26.6%

- Adrenaline doses: 3.3 v 4.4

- Number of shocks by EMS: 5 v 6

- Intermittent ROSC before ED arrival: 33.3% v 26.6%

- Time from 911 call to EMS arrival: 6 v 7 min

- Time from cardiac arrest to 1st shock: 8.5 v 7 min

- EMS scene time: 22.5 v 23 min

- Transport time: 19 v 20 min

- Time to randomisation: 48.5 minutes v 51.8 minutes

- Arriving with ROSC at ED: 0 v 0

Intervention

- ECMO Group (n=15, one patient withdrew consent post randomisation)

- Immediate access to cardiac catheterisation lab

- If 2 or more of: EtCO2 < 10 mmHg, PaO2 < 50 mmHg or SpO2 < 85% and Lactate > 18 mmol/L then further efforts terminated and patient deemed deceased (n=2)

- If above not met, then peripheral veno-arterial ECMO initiated by interventional cardiologists, and coronary angiogram performed with revascularisation if indicated

- Time from 999 call to VA ECMO initiation: 59 min (n=12)

- IABP placed: 40%

Control

- Standard ACLS (n=15)

- Stayed in ED under treatment of emergency physicians

- Treatment continued for 15 minutes or >60 minutes post 911 call

- If arrived with pulses or ROSC achieved > transferred for angiography

- ACLS duration after ED arrival: 28.5 min

- Time of CPR duration from 999 call to death: 81 min

Management common to both groups

- Post angiography care not dictated but followed local protocol in Cardiac ICU

- Included 24 hours of TTM (34 degrees), no neuro-prognostication for 72 hours, CTB on admission and at 72 hours, continuous EEG until awakening

Outcome

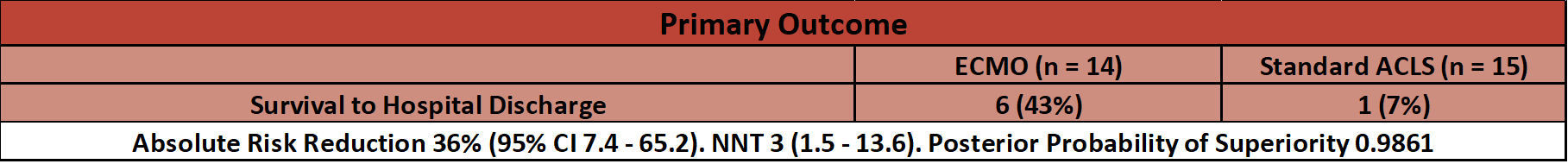

- Primary outcome:

- Survival to hospital discharge – significantly greater in ECMO group

- ECMO vs. ACLS

- 6/14 (43%) vs. 1/15 (7%)

- Posterior probability of 0.9861 of ECMO superiority

- Pre-specified boundary for trial cessation was 0.986 – trial stopped at this point given strong evidence for efficacy (probability greater than pre-specified boundary)

- Fragility index 1

- ECMO vs. ACLS

- Survival to hospital discharge – significantly greater in ECMO group

- Secondary outcomes:

- Analysed with frequentist models

- Cumulative survival significantly better with early ECMO

- Hazard Ratio 0.16 (95% CI 0.06 – 0.41), p < 0.0001

- The 1 survivor in ACLS group died prior to 3 month assessments

- 6 month survival: 43% in ECMO group vs. 0% in ACLS group

- Survivors in ECMO group had good functional outcomes at 6 months

- mRS 1.3

- CPC 1.16

- Length of ICU stay for survivors in ECMO group: 21.5 days (9 – 45)

- Length of hospital stay for survivors in ECMO group: 25.5 days (11 – 48)

- Adverse Events:

- Total number: 166 vs 47 events. A majority of these related to the multi-organ failure and resuscitation attempts (eg. need for vasoactive medication, acute liver injury, need for RRT, rib fractures etc)

- Device related events: 0

- Procedure related events:

- Cracked tubing connector replaced: 1/13 (8%)

- Access site bleeding needing > 3u PRBC: 2/13 (15%)

- IVC trauma, retroperitoneal bleeding: 1/13 (8%)

Authors’ Conclusions

- Early ECMO-facilitated resuscitation for patients with OHCA and refractory VF significantly improved survival to hospital discharge when compared to standard ACLS treatment

Strengths

- Well done randomised trial in a logistically complex cohort of patients

- Randomisation in this trial minimises selection bias, which may be present in observational cohort studies

- Choice of focusing on VF/VT sensible rather than all OHCA as this group seems to have a better chance of survival

- Fast times from randomisation to ECMO initiation (12 minutes)

- Analysed on ITT basis

- Excellent safety reporting measures

- Appendix lists 60 ECMO device related events that need to be recorded

- The statistical plan for randomisation ratios seems complex but given the evidence base prior surrounding ECMO and its improved survival rates then the protocol to continually adapt the numbers of patients randomised to each arm based on regularly assessed probabilities that one treatment is more efficacious (with regards to 6 month survival) is strong

- This would help allay any participants fears that in a trial you have a 50:50 chance of potentially receiving a less effective treatment (based on prior data)

- Non-informative, neutral prior used

- The prior selection can alter Bayesian findings (see Bayesian Statistics explanation)

- Results similar to other trials involving ECMO

- A similar study by the same author in 2017 in which 62 patients were treated with ECMO and PCI with the same inclusion criteria showed 45% survival to hospital discharge and 42% with CPC 1 or 2 at 3 months.

- Slightly different study populations have also shown similar results. Mobile ECMO initiation in Minnesota resulted in 43% hospital discharge and 3 month survival with CPC 1 or 2. The CHEER and 2CHEER trial have shown similarly high survival rates.

- If ongoing studies continue to show this degree of benefit then the NNT will be low (as shown here)

- Further work would also inform the risk of adverse events with ECMO

Weaknesses

- Single center study reduces external validity

- This is especially important in centres where scene and transport time may be longer than ~45 minutes.

- High rates of bystander CPR and fast times to first shock

- Aus-ROC cohort study has bystander CPR rates at 41% (36 – 50%)

- Small numbers of patients

- Given the resources required and frequency of presentations these trials will never randomised very large numbers of patients

- How did early cessation affect the trial outcome?

- Pre-specified boundaries rightly placed for trial safety

- Uncertain effect of trial cessation with only 15 patients in each arm.

- How many more survivors would be needed in ACLS group to reduce the Bayesian probability to under <0.986?

- The probability of superiority was only 0.0001 above the cut off (98.61% likely that ECMO superior to standard ACLS). Would one more survivor in ACLS group have caused the DMSB to continue recruiting until the next interim analysis as the probability of effect would be < 0.986? If so, would these extra 30 patients change the outcome?

- How many more survivors would be needed in ACLS group to reduce the Bayesian probability to under <0.986?

- However, as the authors state, the similarity of these results to the previously published work does increase the robustness

- The results are almost identical to the similar, non randomised study conducted in the same centre in 2017.

- A multi-centre RCT would be ideal following this trial

- It would be interesting to see the breakdown of CPC scores

- Personally, the difference between CPC 1 and 2 would have a very different perceived quality of my life

- No cost analysis done despite being one of the listed secondary outcomes on the trial protocol

- Low fragility index

The Bottom Line

- This randomised trial showed early initiation ECMO resulted in an impressive 43% survival to hospital discharge for refractory shockable OHCA

- The numbers involved were small, and this study was carried out in a centre that was experienced. It is therefore important for other centres to consider their expertise, local protocols and transport times

- Further randomised work is being carried out (e.g. INCEPTION trial) and the results of these ongoing studies should provide a bigger evidence base to inform practice

- I would advocate for the ongoing use of early ECMO in this patient cohort given the poor survival rates for standard ACLS

External Links

- [article] Advanced reperfusion strategies for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and refractory ventricular fibrillation (ARREST): a phase 2, single centre, open-label, randomised controlled trial

- [further reading] ELSO

- [further reading] CPC Score

- [further reading/listening] EDECMO Podcast

Metadata

Summary author: George Walker @hgmwalker89

Summary date: 15th November 2020

Peer-review editor: @david slessor

To whom it may concern,

In my opinion a major issue of this study is, that only the ecmo group underwent coronary angiography. There is a high probability that resuscitative PCI had an impact on the survival rates of the ecmo group.

Especially if you keep in mind that duration of external compression in both groups was quite long (about 50 minutes) and still a good neurological outcome was possible.

In Europe PCI during cardiac arrest is a common practice and even recommended in the ERC Guidelines, so to compare ecmo treatment vs. standard care the control group should also be treated with rescue PCI.

I agree with this comment. Also, the survival (=0) of the control arm was much lower than has been reported and as was used in the power calculation (12%). Finally, there is an issue with the definition of “refractory” ventricular fibrillation as one who has achieved ROSC after the 4th defibrillation was not excluded. It would seem that a uniform definition of “refractory” should mean not achieving ROSC.