Pandemic Triage

A multicentre evaluation of two intensive care unit triage protocols for use in an influenza pandemic

Winston K Cheung. Medical Journal of Australia; August 2012 [3]:178-181. doi:10.5694/mja11.10926]

Clinical Question

- In the event of a viral pandemic, what effect does the use of a triage protocol (specifically the NSW ICU triage protocol) have in increasing ICU bed availability, both in admission and in facilitating ICU discharge?

Background

- During a global pandemic, ICU capacity can become overwhelmed

- This can be mitigated to an extent by reducing ICU demand through cancelling or deferring elective surgery, reserving ICU capacity for patients requiring ICU-specific interventions and reducing the presence of ICU staff on rapid response teams as has been outlined by ANZICS in their recent guideline

- ICU capacity can be increased by utilising additional areas within the hospital to manage ICU patients (e.g theatre recovery), opening existing and non-utilised ICU bed space and facilitating ICU patient discharge

- Additional medical, nursing and allied health staff can be identified (e.g. those with prior experience or working in other critical care areas) and deployed

- COVID-19 positive patients reportedly have an ICU admission rate of 12% of all positive cases and 16% of hospitalised patients based on the recent experiences in Italy

- The UK has some of the lowest ICU beds per head of population in the developed world as demonstrated here and here

- A system of triage can be used to allocate critical care resources to those most likely to benefit during a period of overwhelming demand

- Ethical issues surrounding the use of triage in this context are challenging. It is important that similar ICU admission criteria should apply to all patients across all jurisdictions, and equally to patients with pandemic illness and those with other conditions

- The Ontario Health Plan for an Influenza pandemic (OHPIP) is a triage protocol which was developed following the SARS outbreak Ontario protocol (2005)

- The New South Wales (NSW) triage protocol was developed following the H1N1 pandemic in 2008

- Both protocols employed a combination of exclusion criteria and SOFA scores to determine ICU admission priority

Design

- A prospective evaluation study

- Simulated pandemic model, where usual care, non-pandemic patients were evaluated by an ICU doctor using both the NSW and OHPIP triage protocols, to determine whether they would have qualified for admission to the ICU during a pandemic crisis

- Patients were assessed at admission and at 12 and 72 hours in the case of the NSW protocol; they were assessed at admission and 48 and 120 hours with the Ontario protocol

- The primary outcome measure was increase in ICU bed availability, defined as the percentage of the total bed-days spent by patients in the ICU after the triage protocols had theoretically excluded them from admission or discharged them from the ICU

- Increase in ICU bed availability was calculated as a percentage of the mean number of beds available per ICU per day

- Bed availability results were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test

Setting

- 8 adult, tertiary referral Intensive Care Units in New South Wales and Queensland, Australia in the period after the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic

- September 2009 to May 2010

Population

- Inclusion: All ICU patients were screened

- Exclusion: Patients having elective surgery

- 1262 patients screened; 457 (36.2%) elective surgery patients were excluded

- 805 patients (63.8%) were evaluated using the NSW and OHPIP triage protocols

- 135 ICU beds were available for use

- Mean age of patients was 60.4 (SD 19.4), with a mean APACHE II score of 18 (SD 8)

Intervention

- Application of the NSW triage protocol at ICU admission

- Patients were re-evaluated using the NSW protocol at 12 and 72 hours to assess whether they should be discharged from ICU

- The NSW triage protocol has three tiers and these are designed to be activated in a stepwise, time-based fashion as demand for critical care services increases

Tier 1:

1. Respiratory failure requiring intubation with persistent hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg for adults) unresponsive to fluid therapy after 6–12 hours and signs of additional end-organ dysfunction (eg, oliguria, decreased mental status, cardiac ischaemia)

2. Failure to respond to mechanical ventilation (no improvement in oxygenation or lung compliance) and antibiotics after 72 hours of treatment for a bacterial pathogen

3. Laboratory or clinical evidence of > 4 organ systems failing:

- Pulmonary (acute respiratory distress syndrome, ventilatory failure, refractive hypoxia); Cardiovascular (left ventricular failure, hypotension, new ischaemia); Renal (hyperkalaemia, oliguria despite fluid resuscitation, increasing creatinine level); Hepatic (transaminase > 2 times normal upper limit, increased bilirubin or ammonia levels)

4. Neurological (altered mental status not related to fluid volume status, metabolic or hypoxic source, stroke)

5. Haematological (clinical or laboratory evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation)

6. Cirrhosis with ascites, history of variceal bleeding, fixed coagulopathy, or encephalopathy

Tier 2

- Known congestive cardiac failure with ejection fraction < 25% (or persistent ischaemia unresponsive to therapy and pulmonary oedema)

- Acute renal failure requiring haemodialysis

- Severe chronic lung disease requiring home oxygen therapy

- Immunodeficiency syndromes at a stage where the patient is susceptible to opportunistic pathogens

- Active malignancy with poor potential for survival

- Acute hepatic failure with hyperammonaemia

Tier 3

- Restriction of treatment based on disease-specific epidemiology and survival data for patient subgroups

- Expansion of pre-existing disease classes that will not be offered ventilatory support

- Applying SOFA scoring to the triage process

Control

- Application of the OHPIP triage protocol at ICU admission

- Patients were re-evaluated at 48 and 120 hours to assess whether they should be discharged from ICU

- In order to apply the Ontario protocol, patients had to either require mechanical ventilation or vasopressor therapy

- Exclusion criteria for ICU admission were:

- Severe trauma

- Severe burns with any two of:>40% body surface area affected, inhalational injury and age greater than 60 years

- Cardiac arrest

- Severe baseline cognitive impairment

- Advanced untreatable neuromuscular disease

- Metastatic malignant disease

- Advanced and irreversible immunocompromise

- Severe and irreversible neurological event or condition

- End-stage pre-existant organ failure (NYHA III or IV heart failure, severe COPD, cystic fibrosis with baseline hypoxia, pulmonary fibrosis with baseline hypoxia, primary pulmonary hypertension with associated heart failure

- Child-Pugh B or C cirrhosis

- Age > 85 years

- Elective palliative surgery

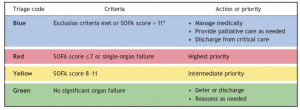

- In addition, patients were assessed with SOFA score at admission and at 48 and 72 hours

- SOFA score > 11: excluded from ICU admission

- SOFA score < 7: highest ICU admission priority

- SOFA score 8-11: intermediate ICU admission priority

- No organ failure: Defer or discharge from ICU

Management common to both groups

- ICU admission and management were not altered by the study as this was a simulated model

- Both protocols employed the following prioritisation criteria, for patients who did not meet the exclusion criteria outlined above:

Outcome

- Primary outcome:

- Using the NSW triage protocol at admission, the increases in ICU bed availability using Tiers 1, 2 and 3 were 3.5%, 14.7% and 22.7%, respectively (p<0.001)

- The incremental increases in ICU bed availability at 12 hours after admission using Tiers 1, 2 and 3 were 19.2%, 16.1% and 14.1%, respectively (p<0.001)

- At 72 hours, there were further non-significant incremental increases in ICU bed availability of 0.9% (p = 0.42), 0.8% (p = 0.33) and 0.7% (P = 0.26)

- Secondary outcome:

- Using the OHPIP at admission, the increase in ICU bed availability was 52.8%

- This represented a significant difference from all tiers of the NSW protocol (p<0.0001)

- Using the protocol at 48 hours and 120 hours provided increased supplemental bed availability of 6.7% and 5.4% respectively

- A 17-bed general ICU would expect to make up to four beds available by using the NSW protocol at admission, depending on which tier was used, and about nine beds using the OHPIP protocol at admission

Authors’ Conclusions

- When tested in a non-influenza pandemic setting, both the NSW and OHPIP triage protocols provided increases in ICU bed availability, but the OHPIP protocol provided the greatest increase overall. Using the NSW triage protocol, ICU bed availability increased as the protocol was escalated

Strengths

- This study addressed an area that has had limited investigation to date

- The results were consistent with a previous retrospective study

- It gives some information on the potential impact of objective triage criteria and how this is likely to impact on available resources. As such, it is useful for pandemic planning

- The patient cohort was a representative sample of ICU patients with a wide range of presentations

Weaknesses

- This data has limited external validity beyond the Australasian setting as ICU admission and discharge practices will vary worldwide

- The simulation does not account for the human factors and difficult ethical dilemmas involved in restricting ICU admission during a crisis

- The definition of severe trauma varies by jurisdiction

- The seniority of clinician performing the triage assessment was not uniform. Ideally, the triaging of ICU patients in this context would be performed by two ICU specialists

- There is the potential for significant inter-operator variability, even with an apparently objective scoring system

- The implementation of a triage protocol will likely have come as part of a phased response. As a result, ICU admission behaviours will likely have deviated from normal practice in the period prior to the activation of a triage protocol. A study of the utility of a triage protocol in the midst of a real pandemic situation would have had more validity

The Bottom Line

- Decisions regarding the most appropriate use of resources are something that intensive care specialists confront every day

- The application of an ICU triage protocol has the potential to significantly reduce ICU admissions during overwhelming demand from a viral pandemic

- The decision on when to activate such a protocol is ethically complex and the implementation should apply to all patients, across all jurisdictions

- I hope that I am not in a situation where I have to implement a triage protocol, but the Ontario model seems to be the most effective in creating additional bed capacity in the Australian setting

External Links

- [article] Original Paper

- [article] Allocating ventilators in a pandemic

- [further reading] Cross-sectional survey on use of triage protocols

- [further reading] ANZICS COVID-19 guidelines

- [further reading] Mauricio Cecconi COVID-19 interview

- [further reading] NSW Influenza Pandemic Guidelines (2009)

Metadata

Summary author: Fraser Magee

Summary date: 18/03/2020

Peer-review editor: Segun Olusanya

Our hospital deployed the Ontario triage tool during March/April, though we never really bothered with SOFA scores. Anecdotally, made a difference in cutting down referrals and giving us clear guidance on when to admit/not admit