Editorial: Early vs Late Renal Replacement Therapy

It’s JAMA vs NEJM and Early vs Late Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT)! And yet the conclusions are conflicting. How can we make sense of this?

In one of our first TBL blog editorials, I shall try to explain some of the differences and decide how to apply this evidence to our patients.

The Articles:

- AKIKI. Gaudry et al. NEJM 2016; published first online. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa160317

- ELAIN. Zarbock et al. JAMA 2016; 315(20):2190-2199. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5828

The TBL Summaries:

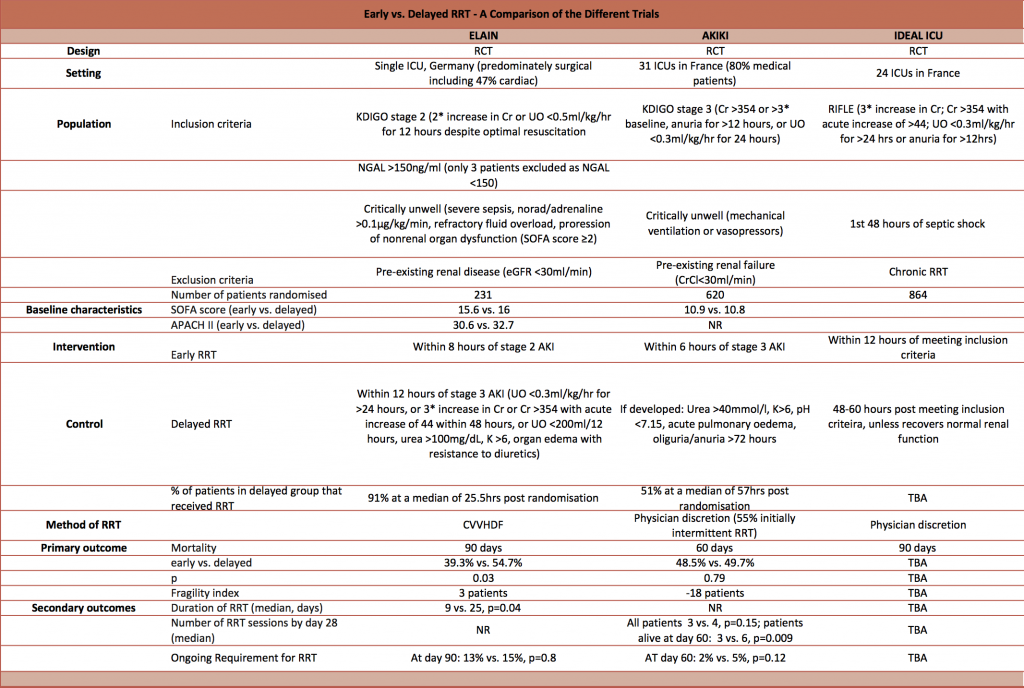

Firstly, here’s a detailed but highly informative comparison table created by Dave Slessor:

What was the theory and hypothesis?

I think this is a key difference.

The AKIKI authors note that observational and indirect data suggest that there may be survival benefit or harm from early RRT – true equipoise. They formed a hypothesis that delayed RRT would confer an absolute survival benefit of at least 15%.

In contrast, the ELAIN authors note evidence from various observational studies and formed a hypothesis that early RRT would confer an absolute survival benefit of 18%.

Although the null hypotheses are the same, it does change how you should appraise the power calculations and subsequent statistics.

Who did they study?

As highlighted in Dave’s table, AKIKI was primarily studying medical patients in multiple centres with sepsis (SOFA scores ~11) whilst ELAIN was studying surgical patients in one centre (SOFA scores ~16). Segun pointed out that the pathophysiology between these two cohorts is probably different.

- Surgical patients: possibly reduced renal blood flow related with stress response pathophysiology

- Medical patients: possibly increased renal blood flow with significant immune complex / toxaemia

What did they study?

Timing of RRT

Both trials defined criteria for the early intervention: these differed slightly such that ELAIN was really early (KDIGO stage 2) and AKIKI was just early (KDIGO stage 3).

The control groups were slightly different too: the ELAIN trial used KDIGO stage 3 (85% patients) or metabolic derangement (15% patients) as the indication for RRT, but the AKIKI trial used metabolic derangement only. This means that the control group in ELAIN was actually a very similar treatment to the AKIKI intervention group.

So ELAIN was really early vs early and AKIKI was early vs conventional.

Delivery of RRT

AKIKI allowed unblinded clinicians to go ahead with whatever mode of RRT they wanted, at whatever dosage. This was mixed intermittent and / or continuous RRT for a median of 4 days. Given that intermittent mode RRT was used extensively, it may be difficult to extrapolate the findings to some Intensive Care Units where continuous mode RRT is used almost exclusively. The exact modalities and dosages delivered were not published. Only 51% of the delayed group actually received RRT.

In contrast, ELAIN defined the RRT modality and dose: continuous vena-venous haemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) at 30 ml/kg/hr with 100% pre-dilution and 1:1 dialysate to replacement fluid. 91% of the delayed group received RRT – a much higher proportion than the AKIKI trial’s delayed group.

How valid are the results?

Both trials provided appropriate screening, selection, randomisation and allocation concealment – these all minimise bias and increase the internal validity of the results.

The lack of defined RRT modality in AKIKI and the lack of blinding (which is unavoidable for pragmatic reasons) may have introduced ascertainment bias: clinicians may have treated one group more favourably in unmeasured ways. This usually exaggerates the measured effect in favour of the primary hypothesis.

The AKIKI trial was powered at 90% and defined a significance level of 5%. The ELAIN trial was powered at 80% with the same significance level. I’ll explain the relevance of this below.

I believe that the potential biases are small in both trials and the internal validity is good enough to accept their results.

What are the result?

The AKIKI trial failed to reject their null hypothesis. The hazard ratio of death at day 60 was 1.03 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.29; p-value = 0.79). Since the 95% CI crosses 1.0, it cannot be concluded that the delayed initiation strategy was better or worse than the early initiation strategy. Given the 90% power of this trial, there is a 10% chance that not rejecting the null hypothesis is wrong.

The ELAIN trial did demonstrate a statistical difference such that the authors rejected their null hypothesis. The hazard ratio of death at day 90 was 0.66 in favour of the early initiation strategy (95% CI 0.45 to 0.97; p-value = 0.03). Another way of phrasing this is that the absolute risk reduction (ARR) was 15.5%, so the number-needed-to-treat to save one patient (NNT) is 7. Again, given the 5% significance level, there is a 5% probability that rejecting the null hypothesis is wrong.

Although the ELAIN trial demonstrated a statistically significant outcome, given the fragility index is just 3 and it is a single centre trial, it is quite likely that a repeat of the trial at another or multiple sites may not find an effect size of the same magnitude.

Can we make sense of it all?

So back to the problem… how can AKIKI conclude that there is no difference whilst ELAIN concludes there is?

I hope I have described how the trials were studying different populations with slightly different interventions on the basis of completely opposing hypotheses. Consequently I think both trials have the correct answer but the questions are different.

- AKIKI: In sick patients that are medical or surgical with sepsis, then I don’t know if early or delayed RRT is the right therapy.

- ELAIN: In really sick patients on a surgical intensive care unit, then I cautiously think very early CVVHDF is the right therapy.

Pingback: LITFL Review 236 – FOAM Ed

Another small trial found no benefit with early rather than late RRT

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26154928

Pingback: RENAL Trial – The Bottom Line

Pingback: BICAR-ICU – The Bottom Line